Canada’s Wage Garnishment Reforms: How Staffing Models Must Adapt to Court Backlogs

Ottawa – August 29, 2025 — Canada’s sweeping reforms to wage garnishment laws, introduced earlier this year, were meant to streamline debt recovery and strengthen protections for workers. But instead of easing the process, the changes have collided with a surge in court backlogs, leaving employers, creditors, and collection agencies scrambling to adapt their staffing models to manage the fallout.

Reforms Meant to Modernize a Strained System

The new wage garnishment framework is the most significant overhaul in decades. For years, critics said Canada’s patchwork of provincial rules left both employers and debtors confused, while creditors often struggled to recover funds.

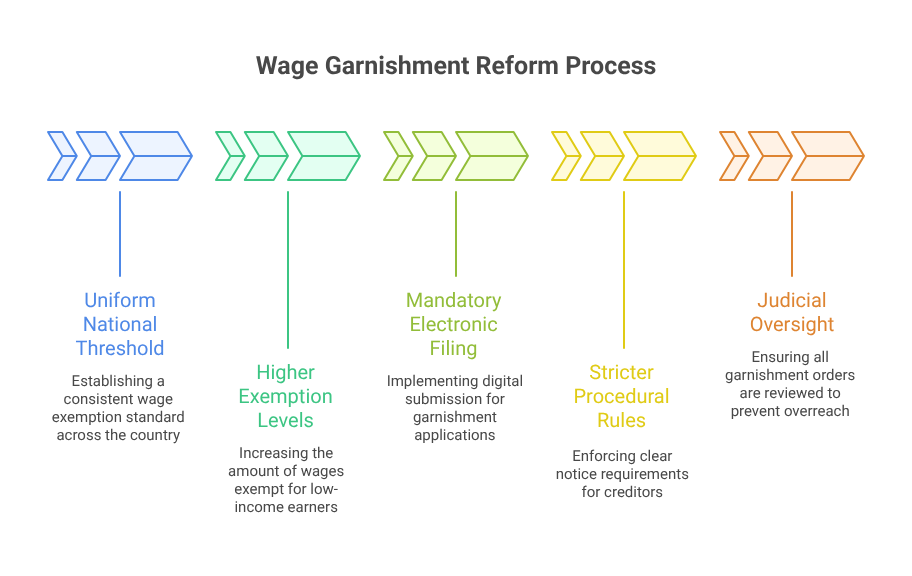

Among the most significant measures in the 2025 reforms are:

- Uniform national threshold for the portion of wages exempt from garnishment.

- Higher exemption levels for low-income earners are aimed at easing financial stress.

- Mandatory electronic filing for most garnishment applications, replacing outdated paper systems.

- Stricter procedural rules on creditors, including clear notice requirements.

- Judicial oversight on all garnishment orders to prevent overreach.

“These reforms were designed to make the system fairer and more transparent,” said a senior official at Employment and Social Development Canada. “The challenge is that implementation requires more judicial involvement at a time when the courts are already strained.”

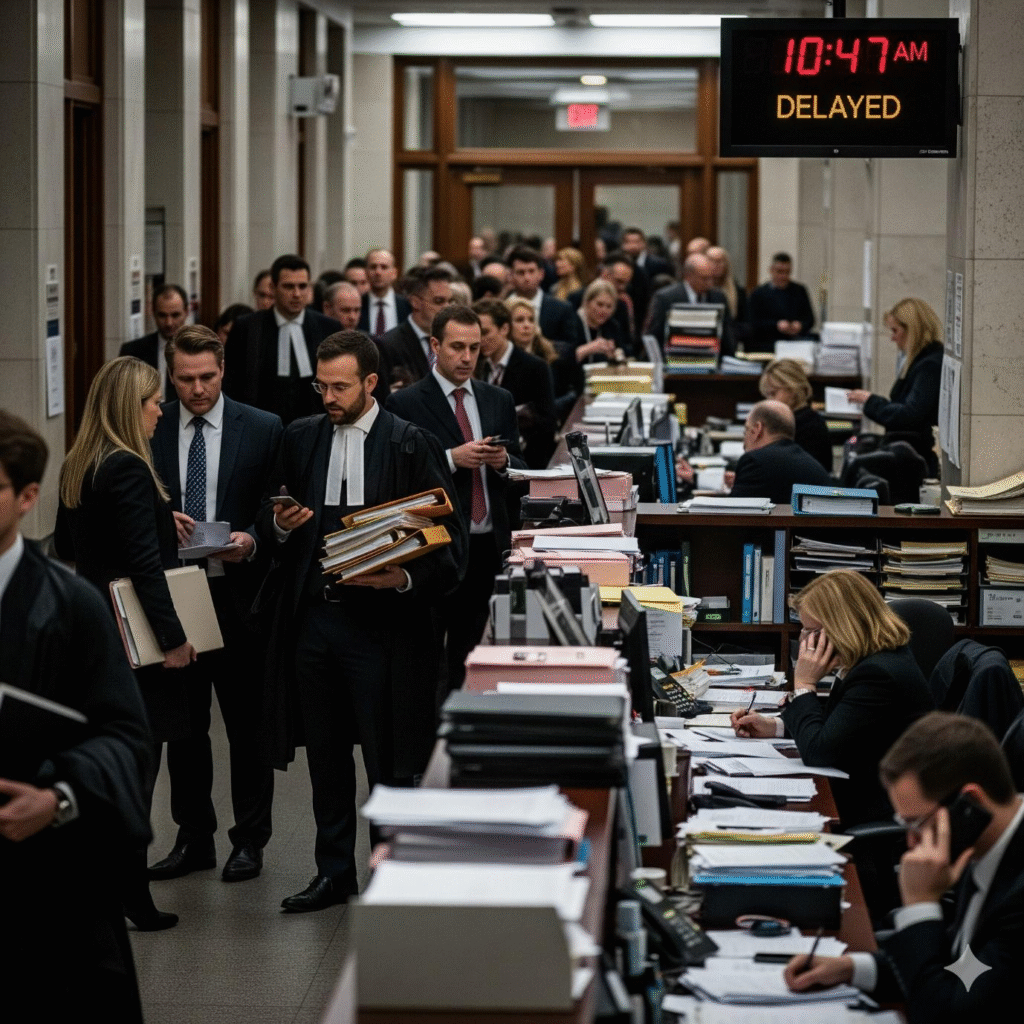

Courts Overwhelmed as Cases Pile Up

Court administrators in several provinces report that the new rules have significantly lengthened processing times. While a garnishment order once took between four and six weeks, creditors now face delays of up to six months.

In Ontario, the Superior Court of Justice is warning creditors to expect extended wait times due to “administrative backlogs.” In Alberta, clerks say new garnishment hearings are being rescheduled into 2026. British Columbia reports similar delays.

“The reforms introduced additional safeguards, but those safeguards require staff and time,” said an Alberta court administrator. “Without new resources, the result is delay across the board.”

The bottlenecks are not limited to garnishment orders. Other civil enforcement matters — including property seizures and judgment renewals — are also moving more slowly, creating ripple effects throughout the legal system.

Creditors Face Mounting Risks

For creditors, the backlogs translate into higher risks and longer recovery timelines. With cases delayed, debtors have more opportunities to change employers, relocate, or restructure their finances before an order takes effect.

“Six months is an eternity in debt collection,” said Mark Ellison, managing director of a Vancouver recovery agency. “By the time the garnishment order is issued, we may be starting from scratch to locate the debtor or verify employment.”

Ellison added that creditors are now spending more on investigative staff just to track debtors during the waiting period. “The costs of delay are being pushed directly onto agencies and, by extension, creditors,” he said.

Employers Struggling With Payroll Compliance

Employers are also under pressure. Garnishment orders that arrive months late often require immediate action, forcing payroll teams to scramble. Remote work has further complicated matters, with employees frequently working across provincial lines.

“We’ve had garnishment orders show up long after employees changed roles or even left the company,” said Karen Liu, HR director for a Toronto-based manufacturer. “Our payroll team is constantly racing to catch up.”

To manage the added burden, many employers are expanding payroll departments or hiring external consultants who specialize in garnishment law. Some are even creating dedicated compliance roles within HR.

Staffing Models in Transition

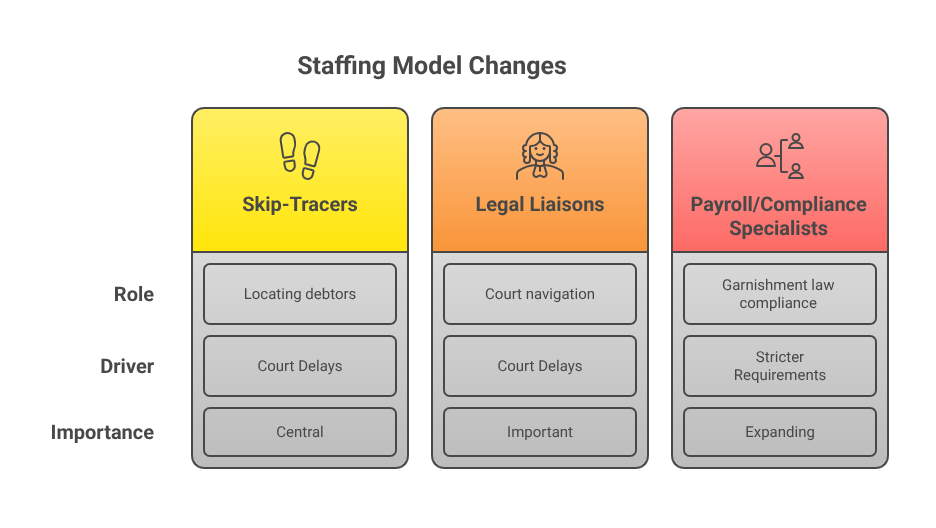

The combination of court delays and stricter requirements has reshaped staffing in debt recovery, law firms, and corporate HR.

Skip-Tracers in Higher Demand

Skip-tracers, once considered supplementary, are now central to recovery operations. Their job: locate debtors who change jobs, addresses, or even provinces during the lengthy court process.

“Skip-tracing is no longer a last resort,” said Ellison. “It’s now part of the standard workflow.”

Legal Liaisons as Court Navigators

Agencies are also hiring legal liaisons and paralegals to monitor court dockets, manage filings, and communicate directly with clerks. These specialists help avoid procedural errors that could result in further delays.

Payroll and Compliance Specialists

On the employer side, payroll teams are expanding to include compliance officers trained specifically in garnishment law. With exemption levels now standardized federally but still subject to provincial interpretation, compliance has become more complex.

Economic Ripple Effects

The ripple effects of the reforms extend beyond staffing. Larger agencies and law firms are absorbing increased operational costs, while smaller firms may struggle to adapt. For employers, especially small businesses, the compliance burden could reduce hiring or limit wage growth.

For consumers, the reforms are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, higher exemption levels protect more of their income. On the other hand, delayed enforcement means interest continues to mount, leaving debtors facing larger balances when garnishment finally begins.

“It feels like a reprieve, but the debt keeps growing in the background,” said Amanda Ross, a financial counsellor in Vancouver. “Many families will be worse off once enforcement eventually happens.”

Uneven Provincial Rollout

Despite federal efforts to create uniformity, provinces retain control over garnishment procedures. Quebec continues to operate under its Civil Code, while provinces such as Saskatchewan and Manitoba interpret exemptions differently.

This has forced national employers and creditors to maintain province-specific compliance protocols, driving up costs.

“The whole point was to make things uniform,” Liu said. “In reality, we’re still dealing with multiple systems.”

Technology Offers Only Partial Relief

Mandatory e-filing was intended to reduce paperwork and accelerate processing, but adoption has been uneven. Some provinces have robust digital portals, while others rely on hybrid systems that still involve manual checks.

Agencies are investing in automation and case-management tools, but experts caution that technology cannot replace human oversight.

“AI can help track filings, but it doesn’t resolve judicial bottlenecks,” said Ellison. “You still need court staff and judges to move cases forward.”

Industry and Consumer Reactions

Reactions to the reforms have been mixed. Industry groups argue the delays threaten financial stability, while consumer advocates say judicial oversight is necessary.

The Canadian Association of Credit Professionals has called for emergency funding to clear backlogs, while some agencies are lobbying for administrative garnishment powers for smaller debts.

Consumer groups oppose that idea. “Removing courts from the process would leave workers vulnerable,” said Sarah Khan of the Canadian Consumer Rights Network. “The reforms were a step in the right direction. The real problem is a lack of investment in the courts.”

Political and Legal Debate

The federal government has acknowledged the challenges but stopped short of promising new funding. Justice Ministry officials say they are monitoring court performance and working with provinces to identify solutions.

Some legal scholars argue the reforms were rushed. “The intent was good, but the execution overlooked the capacity of the courts,” said Professor Daniel Mercer of the University of Ottawa. “It’s a case of policy outpacing infrastructure.”

Looking Ahead

Experts predict the delays will persist well into 2026 unless courts receive additional staffing. In the meantime, employers and creditors are adjusting their models.

“This is the new normal,” said Pelletier, a Montreal-based collections lawyer. “Firms that don’t adapt will struggle.”

Employers are training payroll staff and hiring external consultants, while agencies are expanding skip-tracing teams and paralegal staff.

For debtors, the reforms provide short-term protection but carry long-term risks. “The longer the process drags on, the bigger the debt grows,” Ross warned.

The Road Ahead

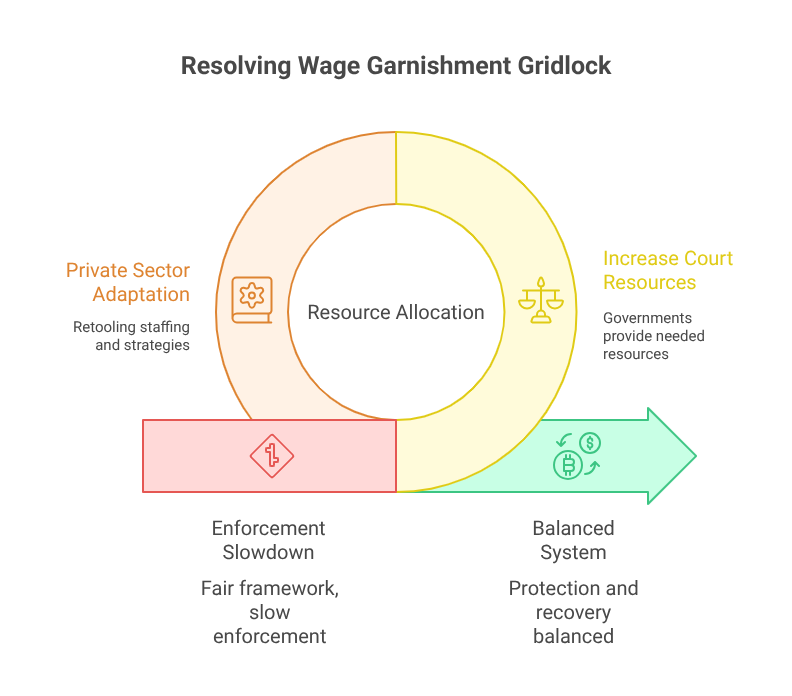

Canada’s wage garnishment reforms represent a milestone in balancing creditor recovery with debtor protection. Yet the lack of court resources has turned reform into gridlock. The country now faces a paradox: a fairer framework that, in practice, has slowed enforcement to a crawl.

The burden has shifted to the private sector, where employers, creditors, and agencies are retooling their staffing strategies to cope. Skip-tracers, paralegals, and payroll specialists — once peripheral — are becoming central to the system’s function.

Whether Canada can strike the intended balance will depend not only on the reforms themselves but on whether governments can provide the resources needed to make them work. Until then, the country’s wage garnishment landscape will remain caught between protection and paralysis.